Fix typos: q-Z --> ctrl-z, Ctrl-c --> ctrl-c |

||

|---|---|---|

| README.md | ||

| cowsay.png | ||

README.md

The Art of Command Line

- Basics

- Everyday use

- Processing files and data

- System debugging

- One-liners

- Obscure but useful

- More resources

- Disclaimer

Fluency on the command line is a skill that is in some ways archaic, but it improves your flexibility and productivity as an engineer in both obvious and subtle ways. This is a selection of notes and tips on using the command-line that I've found useful when working on Linux. Some tips are elementary, and some are fairly specific, sophisticated, or obscure. This page is not long, but if you can use and recall all the items here, you know a lot.

Much of this originally appeared on Quora, but given the interest there, it seems it's worth using Github, where people more talented than I can readily suggest improvements. If you see an error or something that could be better, please submit an issue or PR!

Scope:

- The goals are breadth and brevity. Every tip is essential in some situation or significantly saves time over alternatives.

- This is written for Linux. Many but not all items apply equally to MacOS (or even Cygwin).

- The focus is on interactive Bash, though many tips apply to other shells and to general Bash scripting.

- Descriptions are intentionally minimal, with the expectation you'll use

man,apt-get/yumto install, and Google for more background.

Basics

-

Learn basic Bash. Actually, type

man bashand at least skim the whole thing; it's pretty easy to follow and not that long. Alternate shells can be nice, but bash is powerful and always available (learning only zsh, fish, etc., while tempting on your own laptop, restricts you in many situations, such as using existing servers). -

Learn Vim (

vi). There's really no competition for random Linux editing (even if you use Emacs, a big IDE, or a modern hipster editor most of the time). -

Know ssh, and the basics of passwordless authentication, via

ssh-agent,ssh-add, etc. -

Be familiar with bash job management:

&, ctrl-z, ctrl-c,jobs,fg,bg,kill, etc. -

Basic file management:

lsandls -l(in particular, learn what every column inls -lmeans),less,head,tailandtail -f,lnandln -s(learn the differences and advantages of hard versus soft links),chown,chmod,du(for a quick summary of disk usage:du -sk *),df,mount. -

Basic network management:

iporifconfig,dig. -

Know regular expressions well, and the various flags to

grep/egrep. The-o,-A, and-Boptions are worth knowing. -

Learn to use

apt-getoryum(depending on distro) to find and install packages. And make sure you havepipto install Python-based command-line tools (a few below are easiest to install viapip).

Everyday use

-

In bash, use ctrl-r to search through command history.

-

In bash, use ctrl-w to delete the last word, and ctrl-u to delete the whole line. Use alt-Left and alt-Right to move by word, and ctrl-k to kill to the end of the line. See

man readlinefor all the default keybindings in bash. There are a lot. For example alt-. cycles through previous arguments, and alt-* expands a glob. -

To go back to the previous working directory:

cd - -

If you are halfway through typing a command but change your mind, hit alt-# to add a

#at the beginning and enter it as a comment (or use ctrl-a, #, enter). You can then return to it later via command history. -

Use

xargs(orparallel). It's very powerful. Note you can control how many items execute per line (-L) as well as parallelism (-P). If you're not sure if it'll do the right thing, usexargs echofirst. Also,-I{}is handy. Examples:

find . -name \*.py | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

-

pstree -pis a helpful display of the process tree. -

Use

pgrepandpkillto find or signal processes by name (-fis helpful). -

Know the various signals you can send processes. For example, to suspend a process, use

kill -STOP [pid]. For the full list, seeman 7 signal -

Use

nohupordisownif you want a background process to keep running forever. -

Check what processes are listening via

netstat -lntp. -

See also

lsoffor open sockets and files. -

In bash scripts, use

set -xfor debugging output. Use strict modes whenever possible. Useset -eto abort on errors. Useset -o pipefailas well, to be strict about errors (though this topic is a bit subtle). For more involved scripts, also usetrap. -

In bash scripts, subshells (written with parentheses) are convenient ways to group commands. A common example is to temporarily move to a different working directory, e.g.

# do something in current dir

(cd /some/other/dir; other-command)

# continue in original dir

-

In bash, note there are lots of kinds of variable expansion. Checking a variable exists:

${name:?error message}. For example, if a bash script requires a single argument, just writeinput_file=${1:?usage: $0 input_file}. Arithmetic expansion:i=$(( (i + 1) % 5 )). Sequences:{1..10}. Trimming of strings:${var%suffix}and${var#prefix}. For example ifvar=foo.pdf, thenecho ${var%.pdf}.txtprintsfoo.txt. -

The output of a command can be treated like a file via

<(some command). For example, compare local/etc/hostswith a remote one:

diff /etc/hosts <(ssh somehost cat /etc/hosts)

-

Know about "here documents" in bash, as in

cat <<EOF .... -

In Bash, redirect both standard output and standard error via:

some-command >logfile 2>&1. Often, to ensure a command does not leave an open file handle to standard input, tying it to the terminal you are in, it is also good practice to add</dev/null. -

Use

man asciifor a good ASCII table, with hex and decimal values. -

Use

screenortmuxto multiplex the screen, especially useful on remote ssh sessions and to detach and re-attach to a session. A more minimal alternative for session persistence only isdtach. -

In ssh, knowing how to port tunnel with

-Lor-D(and occasionally-R) is useful, e.g. to access web sites from a remote server. -

It can be useful to make a few optimizations to your ssh configuration; for example, this

~/.ssh/configcontains settings to avoid dropped connections in certain network environments, not require confirmation connecting to new hosts, forward authentication, and use compression (which is helpful with scp over low-bandwidth connections):

TCPKeepAlive=yes

ServerAliveInterval=15

ServerAliveCountMax=6

StrictHostKeyChecking=no

Compression=yes

ForwardAgent=yes

- To get the permissions on a file in octal form, which is useful for system configuration but not available in

lsand easy to bungle, use something like

stat -c '%A %a %n' /etc/timezone

-

For interactive selection of values from the output of another command, use

percol. -

For interaction with files based on the output of another command (like

git), usefpp(PathPicker).

Processing files and data

-

To locate a file by name in the current directory,

find -iname *something* .(or similar). To find a file anywhere by name, uselocate something(but bear in mindupdatedbmy not have indexed recently created files). -

For general searching through source or data files (more advanced than

grep -r), useag. -

To convert HTML to text:

lynx -dump -stdin -

For Markdown, HTML, and all kinds of document conversion, try

pandoc. -

If you must handle XML,

xmlstarletis old but good. -

For JSON, use

jq. -

For Amazon S3,

s3cmdis convenient ands4cmdis faster. Amazon'sawsis essential for other AWS-related tasks. -

Know about

sortanduniq, including uniq's-uand-doptions -- see one-liners below. -

Know about

cut,paste, andjointo manipulate text files. Many people usecutbut forget aboutjoin. -

Know that locale affects a lot of command line tools, including sorting order and performance. Most Linux installations will set

LANGor other locale variables to a local setting like US English. This can make sort or other commands run many times slower. (Note that even if you use UTF-8 text, you can safely sort by ASCII order for many purposes.) To disable slow i18n routines and use traditional byte-based sort order, useexport LC_ALL=C(in fact, consider putting this in your~/.bashrc). -

Know basic

awkandsedfor simple data munging. For example, summing all numbers in the third column of a text file:awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }'. This is probably 3X faster and 3X shorter than equivalent Python. -

To replace all occurrences of a string in place, in one or more files:

perl -pi.bak -e 's/old-string/new-string/g' my-files-*.txt

- To rename many files at once according to a pattern, use

rename. For complex renames,reprenmay help.

# Recover backup files foo.bak -> foo:

rename 's/\.bak$//' *.bak

# Full rename of filenames, directories, and contents foo -> bar:

repren --full --preserve-case --from foo --to bar .

-

Use

shufto shuffle or select random lines from a file. -

Know

sort's options. Know how keys work (-tand-k). In particular, watch out that you need to write-k1,1to sort by only the first field;-k1means sort according to the whole line. -

Stable sort (

sort -s) can be useful. For example, to sort first by field 2, then secondarily by field 1, you can usesort -k1,1 | sort -s -k2,2 -

If you ever need to write a tab literal in a command line in bash (e.g. for the -t argument to sort), press ctrl-v [Tab] or write

$'\t'(the latter is better as you can copy/paste it). -

For binary files, use

hdfor simple hex dumps andbvifor binary editing. -

Also for binary files,

strings(plusgrep, etc.) lets you find bits of text. -

To convert text encodings, try

iconv. Oruconvfor more advanced use; it supports some advanced Unicode things. For example, this command lowercases and removes all accents (by expanding and dropping them):

uconv -f utf-8 -t utf-8 -x '::Any-Lower; ::Any-NFD; [:Nonspacing Mark:] >; ::Any-NFC; ' < input.txt > output.txt

- To split files into pieces, see

split(to split by size) andcsplit(to split by a pattern).

System debugging

-

For web debugging,

curlandcurl -Iare handy, or theirwgetequivalents, or the more modernhttpie. -

To know disk/cpu/network status, use

iostat,netstat,top(or the betterhtop), and (especially)dstat. Good for getting a quick idea of what's happening on a system. -

To know memory status, run and understand the output of

freeandvmstat. In particular, be aware the "cached" value is memory held by the Linux kernel as file cache, so effectively counts toward the "free" value. -

Java system debugging is a different kettle of fish, but a simple trick on Oracle's and some other JVMs is that you can run

kill -3 <pid>and a full stack trace and heap summary (including generational garbage collection details, which can be highly informative) will be dumped to stderr/logs. -

Use

mtras a better traceroute, to identify network issues. -

For looking at why a disk is full,

ncdusaves time over the usual commands likedu -sh *. -

To find which socket or process is using bandwidth, try

iftopornethogs. -

The

abtool (comes with Apache) is helpful for quick-and-dirty checking of web server performance. For more complex load testing, trysiege. -

For more serious network debugging,

wiresharkortshark. -

Know about

straceandltrace. These can be helpful if a program is failing, hanging, or crashing, and you don't know why, or if you want to get a general idea of performance. Note the profiling option (-c), and the ability to attach to a running process (-p). -

Know about

lddto check shared libraries etc. -

Know how to connect to a running process with

gdband get its stack traces. -

Use

/proc. It's amazingly helpful sometimes when debugging live problems. Examples:/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/xxx/cwd,/proc/xxx/exe,/proc/xxx/fd/,/proc/xxx/smaps. -

When debugging why something went wrong in the past,

sarcan be very helpful. It shows historic statistics on CPU, memory, network, etc. -

For deeper systems and performance analyses, look at

stap(SystemTap),perf, andsysdig. -

Confirm what Linux distribution you're using (works on most distros):

lsb_release -a -

Use

dmesgwhenever something's acting really funny (it could be hardware or driver issues).

One-liners

A few examples of piecing together commands:

- It is remarkably helpful sometimes that you can do set intersection, union, and difference of text files via

sort/uniq. Supposeaandbare text files that are already uniqued. This is fast, and works on files of arbitrary size, up to many gigabytes. (Sort is not limited by memory, though you may need to use the-Toption if/tmpis on a small root partition.) See also the note aboutLC_ALLabove.

cat a b | sort | uniq > c # c is a union b

cat a b | sort | uniq -d > c # c is a intersect b

cat a b b | sort | uniq -u > c # c is set difference a - b

- Summing all numbers in the third column of a text file (this is probably 3X faster and 3X less code than equivalent Python):

awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }' myfile

- If want to see sizes/dates on a tree of files, this is like a recursive

ls -lbut is easier to read thanls -lR:

find . -type f -ls

- Use

xargsorparallelwhenever you can. Note you can control how many items execute per line (-L) as well as parallelism (-P). If you're not sure if it'll do the right thing, use xargs echo first. Also,-I{}is handy. Examples:

find . -name \*.py | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

- Say you have a text file, like a web server log, and a certain value that appears on some lines, such as an

acct_idparameter that is present in the URL. If you want a tally of how many requests for eachacct_id:

cat access.log | egrep -o 'acct_id=[0-9]+' | cut -d= -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

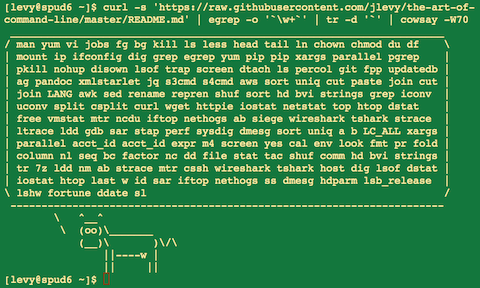

- Run this function to get a random tip from this document (parses Markdown and extracts an item):

function taocl() {

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line/master/README.md |

pandoc -f markdown -t html |

xmlstarlet fo --html --dropdtd |

xmlstarlet sel -t -v "(html/body/ul/li[count(p)>0])[$RANDOM mod last()+1]" |

xmlstarlet unesc | fmt 80

}

Obscure but useful

-

expr: perform arithmetic or boolean operations or evaluate regular expressions -

m4: simple macro processor -

screen: powerful terminal multiplexing and session persistence -

yes: print a string a lot -

cal: nice calendar -

env: run a command (useful in scripts) -

look: find English words (or lines in a file) beginning with a string -

cutand paste and join: data manipulation -

fmt: format text paragraphs -

pr: format text into pages/columns -

fold: wrap lines of text -

column: format text into columns or tables -

expandand unexpand: convert between tabs and spaces -

nl: add line numbers -

seq: print numbers -

bc: calculator -

factor: factor integers -

nc: network debugging and data transfer -

dd: moving data between files or devices -

file: identify type of a file -

stat: file info -

tac: print files in reverse -

shuf: random selection of lines from a file -

comm: compare sorted files line by line -

hdandbvi: dump or edit binary files -

strings: extract text from binary files -

tr: character translation or manipulation -

iconvor uconv: conversion for text encodings -

splitand csplit: splitting files -

7z: high-ratio file compression -

ldd: dynamic library info -

nm: symbols from object files -

ab: benchmarking web servers -

strace: system call debugging -

mtr: better traceroute for network debugging -

cssh: visual concurrent shell -

wiresharkandtshark: packet capture and network debugging -

hostanddig: DNS lookups -

lsof: process file descriptor and socket info -

dstat: useful system stats -

iostat: CPU and disk usage stats -

htop: improved version of top -

last: login history -

w: who's logged on -

id: user/group identity info -

sar: historic system stats -

iftopornethogs: network utilization by socket or process -

ss: socket statistics -

dmesg: boot and system error messages -

hdparm: SATA/ATA disk manipulation/performance -

lsb_release: Linux distribution info -

lshw: hardware information -

fortune,ddate, andsl: um, well, it depends on whether you consider steam locomotives and Zippy quotations "useful"

More resources

- awesome-shell: A curated list of shell tools and resources.

- Strict mode for writing better shell scripts.

Disclaimer

With the exception of very small tasks, code is written so others can read it. The fact you can do something in Bash doesn't necessarily mean you should! ;)